Follow the Money

Corruption in Iraq is out of control. But will the United States join efforts to clamp down on it?

Michael Hirsh Newsweek

By many accounts, Custer Battles was a nightmare contractor in Iraq. The company's two principals, Mike Battles and Scott Custer, overcharged occupation authorities by millions of dollars, according to a complaint from two former employees. The firm double-billed for salaries and repainted the Iraqi Airways forklifts they found at Baghdad airport—which Custer Battles was contracted to secure—then leased them back to the U.S. government, the complaint says. In the fall of 2004, Deputy General Counsel Steven Shaw of the Air Force asked that the firm be banned from future U.S. contracts, saying Custer Battles had also "created sham companies, whereby [it] fraudulently increased profits by inflating its claimed costs." An Army inspector general, Col. Richard Ballard, concluded as early as November 2003 that the security outfit was incompetent and refused to obey Joint Task Force 7 orders: "What we saw horrified us," Ballard wrote to his superiors in an e-mail obtained by NEWSWEEK.

Yet when the two whistle-blowers sued Custer Battles on behalf of the U.S. government—under a U.S. law intended to punish war profiteering and fraud—the Bush administration declined to take part. "The government has not lifted a finger to get back the $50 million Custer Battles defrauded it of," says Alan Grayson, a lawyer for the two whistle-blowers, Pete Baldwin and Robert Isakson. In recent months the judge in the case, T. S. Ellis III of the U.S. District Court in Virginia, has twice invited the Justice Department to join the lawsuit without response. Even an administration ally, Sen. Charles Grassley, demanded to know in a Feb. 17 letter to Attorney General Alberto Gonzales why the government wasn't backing up the lawsuit. Because this is a "seminal" case—the first to be unsealed against an Iraq contractor—"billions of taxpayer dollars are at stake" based on the precedent it could set, the Iowa Republican said.

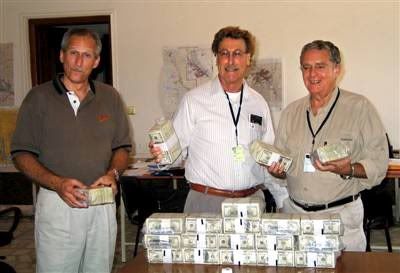

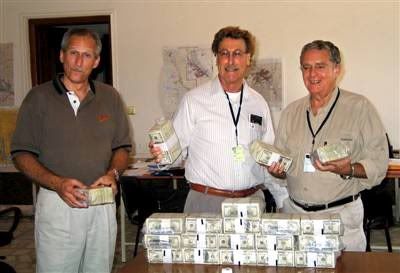

'Fraud-free zone': Willis (center) in Iraq with two CPA colleagues, preparing to pay a contractor in 2003

Why hasn't the administration joined the case? It has argued privately that the occupation government, known as the Coalition Provisional Authority, was a multinational institution, not an arm of the U.S. government. So the U.S. government was not technically defrauded. Lawyers for the whistle-blowers point out, however, that President George W. Bush signed a 2003 law authorizing $18.7 billion to go to U.S. authorities in Iraq, including the CPA, "as an entity of the United States government." And several contracts with Custer Battles refer to the other party as "the United States of America." Pressure has been building on the administration to join the case—or at least to file a brief saying publicly if it believes defrauding the CPA is the same as defrauding the United States. The judge's latest deadline for that brief is this Friday. But a Justice Department spokesman said last week the government "could" still refuse to take part. "I'll bet you $50 they will not show up," says Richard Sauber, a lawyer for Custer Battles, which is still operating in Iraq. (He also rejects the charges of fraud and incompetence.)

The administration's reluctance to prosecute has turned the Iraq occupation into a "free-fraud zone," says former CPA senior adviser Franklin Willis. After the fall of Baghdad, there was no Iraqi law because Saddam Hussein's regime was dead. But if no U.S. law applied either, then everything was permissible, says Willis. The former CPA official compares Iraq to the "Wild West," saying he delivered one $2 million payment to Custer Battles in bricks of cash. ("We called Mike Battles in and said, 'Bring a bag'," Willis told Congress in February.) Willis and other critics worry that with just $4.1 billion of the $18.7 billion spent so far, the U.S. legal stance will open the door to much more fraud in the future. "If urgent steps are not taken, Iraq ... will become the biggest corruption scandal in history," warned the anti-corruption group Transparency International in a recent report. Grassley adds that if the government decides the False Claims Act doesn't apply to Iraq, "any recovery for fraud, waste and abuse of taxpayer dollars ... would be prohibited."

More than U.S. money is at stake. The administration has harshly criticized the United Nations over hundreds of millions stolen from the Oil-for-Food Program under Saddam. But the successor to Oil-for-Food created under the occupation, called the Development Fund for Iraq, could involve billions of potentially misused dollars. On Jan. 30, the former CPA's own inspector general, Stuart Bowen, concluded that occupation authorities accounted poorly for $8.8 billion in these Iraqi funds. "The CPA did not implement adequate financial controls," Bowen said. U.S. officials argue that it was impossible, in a war environment, to have such controls. Yet now the Bush administration is either ignoring or stalling inquiries into the use of these Iraqi oil funds, according to reports by Democratic Rep. Henry Waxman, and others.

In one case, the Pentagon's own Defense Contract Audit Agency found that the leading U.S. contractor in Iraq, Halliburton subsidiary KBR, overcharged Iraq occupation authorities by $108 million for a task order to deliver fuel. Yet the Pentagon permitted KBR to redact—or black out—almost all negative references to the company in this Oct. 8, 2004, audit. These included any mention of the $108 million in alleged overcharges and the audit's clear conclusion that KBR's price-supporting data were "not adequate." The Defense Department then forwarded this censored version to a U.N. monitoring board that Washington had agreed to under U.N. Resolution 1483. Normally, an audited company is allowed to censor its proprietary or personal information, but "these redactions went beyond anything U.S. law would allow," says Tom Susman, a Washington expert. Halliburton spokeswoman Wendy Hall insists that the company had the right to make such redactions because the audit was "predecisional" and "represented only one side of the case." Hall also denies the company overcharged.

The U.N. audit team, called the International Advisory and Monitoring Board, is angry over these heavily censored reports, officials tell NEWSWEEK. The board last fall asked that a special auditor be hired. But the Pentagon has yet to award that contract after six months of delays. A Pentagon spokeswoman says the U.N. audit team "agreed that the [KBR] information provided was responsive to their request." A U.N. spokesman says this is untrue.

The administration's seemingly detached approach to these cases could have other implications. NEWSWEEK has learned that federal prosecutors plan to indict several U.S. contractors in Iraq on criminal charges but that these could be undercut if the court rules in the Custer Battles case that the CPA was not a U.S. government arm. "If you make the CPA a U.S. entity, you open the door to all sorts of liability claims. But if it's not a U.S. entity, then you can't parade these people through the court," says Jim Mitchell of the CPA inspector general's office. And that could mean Custer Battles and other companies will ultimately answer to no one.

With Babak Dehghanpisheh

© 2005 Newsweek, Inc.

Michael Hirsh Newsweek

By many accounts, Custer Battles was a nightmare contractor in Iraq. The company's two principals, Mike Battles and Scott Custer, overcharged occupation authorities by millions of dollars, according to a complaint from two former employees. The firm double-billed for salaries and repainted the Iraqi Airways forklifts they found at Baghdad airport—which Custer Battles was contracted to secure—then leased them back to the U.S. government, the complaint says. In the fall of 2004, Deputy General Counsel Steven Shaw of the Air Force asked that the firm be banned from future U.S. contracts, saying Custer Battles had also "created sham companies, whereby [it] fraudulently increased profits by inflating its claimed costs." An Army inspector general, Col. Richard Ballard, concluded as early as November 2003 that the security outfit was incompetent and refused to obey Joint Task Force 7 orders: "What we saw horrified us," Ballard wrote to his superiors in an e-mail obtained by NEWSWEEK.

Yet when the two whistle-blowers sued Custer Battles on behalf of the U.S. government—under a U.S. law intended to punish war profiteering and fraud—the Bush administration declined to take part. "The government has not lifted a finger to get back the $50 million Custer Battles defrauded it of," says Alan Grayson, a lawyer for the two whistle-blowers, Pete Baldwin and Robert Isakson. In recent months the judge in the case, T. S. Ellis III of the U.S. District Court in Virginia, has twice invited the Justice Department to join the lawsuit without response. Even an administration ally, Sen. Charles Grassley, demanded to know in a Feb. 17 letter to Attorney General Alberto Gonzales why the government wasn't backing up the lawsuit. Because this is a "seminal" case—the first to be unsealed against an Iraq contractor—"billions of taxpayer dollars are at stake" based on the precedent it could set, the Iowa Republican said.

'Fraud-free zone': Willis (center) in Iraq with two CPA colleagues, preparing to pay a contractor in 2003

Why hasn't the administration joined the case? It has argued privately that the occupation government, known as the Coalition Provisional Authority, was a multinational institution, not an arm of the U.S. government. So the U.S. government was not technically defrauded. Lawyers for the whistle-blowers point out, however, that President George W. Bush signed a 2003 law authorizing $18.7 billion to go to U.S. authorities in Iraq, including the CPA, "as an entity of the United States government." And several contracts with Custer Battles refer to the other party as "the United States of America." Pressure has been building on the administration to join the case—or at least to file a brief saying publicly if it believes defrauding the CPA is the same as defrauding the United States. The judge's latest deadline for that brief is this Friday. But a Justice Department spokesman said last week the government "could" still refuse to take part. "I'll bet you $50 they will not show up," says Richard Sauber, a lawyer for Custer Battles, which is still operating in Iraq. (He also rejects the charges of fraud and incompetence.)

The administration's reluctance to prosecute has turned the Iraq occupation into a "free-fraud zone," says former CPA senior adviser Franklin Willis. After the fall of Baghdad, there was no Iraqi law because Saddam Hussein's regime was dead. But if no U.S. law applied either, then everything was permissible, says Willis. The former CPA official compares Iraq to the "Wild West," saying he delivered one $2 million payment to Custer Battles in bricks of cash. ("We called Mike Battles in and said, 'Bring a bag'," Willis told Congress in February.) Willis and other critics worry that with just $4.1 billion of the $18.7 billion spent so far, the U.S. legal stance will open the door to much more fraud in the future. "If urgent steps are not taken, Iraq ... will become the biggest corruption scandal in history," warned the anti-corruption group Transparency International in a recent report. Grassley adds that if the government decides the False Claims Act doesn't apply to Iraq, "any recovery for fraud, waste and abuse of taxpayer dollars ... would be prohibited."

More than U.S. money is at stake. The administration has harshly criticized the United Nations over hundreds of millions stolen from the Oil-for-Food Program under Saddam. But the successor to Oil-for-Food created under the occupation, called the Development Fund for Iraq, could involve billions of potentially misused dollars. On Jan. 30, the former CPA's own inspector general, Stuart Bowen, concluded that occupation authorities accounted poorly for $8.8 billion in these Iraqi funds. "The CPA did not implement adequate financial controls," Bowen said. U.S. officials argue that it was impossible, in a war environment, to have such controls. Yet now the Bush administration is either ignoring or stalling inquiries into the use of these Iraqi oil funds, according to reports by Democratic Rep. Henry Waxman, and others.

In one case, the Pentagon's own Defense Contract Audit Agency found that the leading U.S. contractor in Iraq, Halliburton subsidiary KBR, overcharged Iraq occupation authorities by $108 million for a task order to deliver fuel. Yet the Pentagon permitted KBR to redact—or black out—almost all negative references to the company in this Oct. 8, 2004, audit. These included any mention of the $108 million in alleged overcharges and the audit's clear conclusion that KBR's price-supporting data were "not adequate." The Defense Department then forwarded this censored version to a U.N. monitoring board that Washington had agreed to under U.N. Resolution 1483. Normally, an audited company is allowed to censor its proprietary or personal information, but "these redactions went beyond anything U.S. law would allow," says Tom Susman, a Washington expert. Halliburton spokeswoman Wendy Hall insists that the company had the right to make such redactions because the audit was "predecisional" and "represented only one side of the case." Hall also denies the company overcharged.

The U.N. audit team, called the International Advisory and Monitoring Board, is angry over these heavily censored reports, officials tell NEWSWEEK. The board last fall asked that a special auditor be hired. But the Pentagon has yet to award that contract after six months of delays. A Pentagon spokeswoman says the U.N. audit team "agreed that the [KBR] information provided was responsive to their request." A U.N. spokesman says this is untrue.

The administration's seemingly detached approach to these cases could have other implications. NEWSWEEK has learned that federal prosecutors plan to indict several U.S. contractors in Iraq on criminal charges but that these could be undercut if the court rules in the Custer Battles case that the CPA was not a U.S. government arm. "If you make the CPA a U.S. entity, you open the door to all sorts of liability claims. But if it's not a U.S. entity, then you can't parade these people through the court," says Jim Mitchell of the CPA inspector general's office. And that could mean Custer Battles and other companies will ultimately answer to no one.

With Babak Dehghanpisheh

© 2005 Newsweek, Inc.

<< Home