KATRINA / "THIS COULD BE THE ONE"

The Steady Buildup to a City's Chaos * Confusion Reigned At Every Level Of Government

Walter Maestri had dreaded this call for a decade, ever since he took over emergency management for Jefferson Parish, a marshy collection of suburbs around New Orleans. It was Friday night, Aug. 26, and his friend Max Mayfield was on the line. Mayfield is the head of the National Hurricane Center, and he wasn't calling to chat.

"Walter," Mayfield said, "get ready."

"What do you mean?" Maestri asked, though he already knew the answer.

Hurricane Katrina had barreled into the Gulf of Mexico, and Mayfield's latest forecast had it smashing into New Orleans as a Category 4 or 5 storm Monday morning. Maestri already had 10,000 body bags in his parish, in case he ever got a call like this.

"This could be the one," Mayfield told him.

Maestri heard himself gasp: "Oh, my God."

In July 2004, Maestri had participated in an exercise called Hurricane Pam, a simulation of a Category 3 storm drowning New Orleans. Emergency planners had concluded that a real Pam would create a flood of unimaginable proportions, killing tens of thousands of people, wiping out hundreds of thousands of homes, shutting down southeast Louisiana for months.

The practice run for a New Orleans apocalypse had been commissioned by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the federal government's designated disaster shop. But the funding ran out and the doomsday scenario became just another prescient -- but buried -- government report. Now, practice was over.

And Pam's lessons had not been learned.

As the floodwaters recede and the dead are counted, what went wrong during a terrible week that would render a modern American metropolis of nearly half a million people uninhabitable and set off the largest exodus of people since the Civil War, is starting to become clear. Federal, state and local officials failed to heed forecasts of disaster from hurricane experts. Evacuation plans, never practical, were scrapped entirely for New Orleans's poorest and least able. And once floodwaters rose, as had been long predicted, the rescue teams, medical personnel and emergency power necessary to fight back were nowhere to be found.

Compounding the natural catastrophe was a man-made one: the inability of the federal, state and local governments to work together in the face of a disaster long foretold.

In many cases, resources that were available were not used, whether Amtrak trains that could have taken evacuees to safety before the storm or the U.S. military's 82nd Airborne division, which spent days on standby waiting for orders that never came. Communications were so impossible the Army Corps of Engineers was unable to inform the rest of the government for crucial hours that levees in New Orleans had been breached.

The massive rescue effort that resulted was a fugue of improvisation, by fleets of small boats that set sail off highway underpasses and angry airport directors and daredevil helicopter pilots. Tens of thousands were saved as the city swamped; they were plucked from rooftops and bused, eventually, out of the disaster zone.

But it was an infuriating time of challenge when government seemed unable to meet its basic compact with its citizens. After the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, an entirely new Department of Homeland Security had been created, charged with doing better the next time, whether the crisis was another terrorist attack or not. Its new plan for safeguarding the nation, unveiled just this year, clearly spelled out the need to take charge in assisting state and local governments sure to be "overwhelmed" by a cataclysmic event.

Instead, confusion reigned at every level of officialdom, according to dozens of interviews with participants in Louisiana, Mississippi and Washington. "No one had access. . . . No one had communication. . . . Nobody knew where the people were," recalled Secretary of Health and Human Services Mike Leavitt, whose department did not declare the Gulf Coast a public health emergency until two days after the storm.

Despite pleas by Bush administration officials to refrain from "the blame game," mutual recriminations among officeholders began even before New Orleans's trapped residents had been rescued. The White House secretly debated federalizing authority in a city under the control of a Democratic mayor and governor, and critics in both parties assailed FEMA and raised questions about President Bush.

That Friday, as Maestri prepared for the Big One, he had known that his region's survival would depend on the federal response. After Hurricane Pam, FEMA officials had concluded that local authorities might be on their own for 48 or even 60 hours after a real storm, but they had assured Maestri that the cavalry would swoop in after that, and take care of the region's needs.

"Like a fool, I believed them," Maestri said last week.

Friday, Aug. 26

'Why aren't we treating this as a bigger emergency?'

At 5 a.m., Hurricane Katrina entered the Gulf of Mexico with the Louisiana coastline in its sights. In Elmwood, La., dozens of federal, state and local disaster officials were meeting to discuss storm response, but their topic was Tropical Storm Cindy, which had come ashore on July 5. While leaders of Louisiana's Office of Homeland Security and the National Guard tracked Katrina with a handheld device, local emergency managers learned how they could submit claims for Cindy's relatively modest damage.

"Shouldn't we just apply for Katrina money now?" quipped Jim Baker, operations superintendent for the East Jefferson Levee District.

As the storm track hooked toward New Orleans, the disaster officials began passing the handheld device around the room. It was becoming clear that Katrina was no joking matter. But it was already getting late to be getting serious.

After the Hurricane Pam drill, disaster planners had concluded that evacuating New Orleans could take as long as 72 hours before a storm's landfall. By midday Friday, it was 66 hours before Katrina would end up hitting, and the threat was just starting to sink in. "With this storm, people should have evacuated no later than Friday," said a senior official in a neighboring state. "Anything after that was very risky."

In Washington, the cumbersome machinery of catastrophe began to crank up.

At the Department of Homeland Security, the 180,000-employee bureaucracy created after the Sept. 11 attacks, that meant convening the Interagency Incident Management Group. About 20 federal agencies had seats at the table, from the State Department to the Veterans Affairs Department.

FEMA was still the lead disaster agency, as it had been since 1979, but was now just a piece of DHS. Instead of Cabinet-level status and a direct line to the president, its director -- Michael D. Brown, a lawyer and former Arabian horse association official -- was an undersecretary. Funding had been cut over the past four years for FEMA's disaster-relief mission, and experienced personnel had left in droves. While experts who closely tracked FEMA had publicly fretted about the agency's reduced status, their warnings had not received widespread public attention.

By Friday, FEMA's emergency headquarters for Katrina was already running; technically, the agency was at level one, its highest level of alert.

But as the headquarters staff came in, there was a strange sense of inaction, as if "nobody's turning the key to start the engine," said one team leader, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. For his group, Friday was a day to sit around wondering, "Why aren't we treating this as a bigger emergency? Why aren't we doing anything?"

That evening, shortly before Max Mayfield made his call to Walter Maestri, Louisiana Gov. Kathleen Babineaux Blanco (D) declared a state of emergency.

Saturday, Aug. 27

'This is not a test: This is the real deal.'

By morning, Katrina was already a Category 3 hurricane, and Mayfield was predicting it could make landfall near New Orleans as an even deadlier Category 4. On FEMA's daily noon videoconference, he looked around the U-shaped conference table in Washington and saw a lot of newcomers to the disaster world among the agency's political appointees. But he knew many of the professionals listening in from the Gulf states had been through his hurricane prep course. They knew this was no drill.

"The emergency guys, they know what a Cat 4 is," Mayfield recalled. And this had the potential to be a Category 5, only the fourth in U.S. history. "This one is different," Mayfield told the videoconference. "It's strong, but it's also much, much larger."

When talk turned to New Orleans, Mayfield mentioned the possibility of water overwhelming the levees; his center soon forecast a storm surge as high as 25 feet, far above the 17-foot clearance for most of the city's storm protection. "Clearly on Saturday, we knew it was going to be the Big One," recalled Jack Colley, Texas's veteran disaster man. "We were very convinced this was going to be a very catastrophic event."

The challenge was to get people out of harm's way. All day long, Louisiana officials announced voluntary evacuations, and Blanco implemented a "contra-flow" traffic plan to help as coastal residents reach higher grounds. Maestri said there was no point in ordering mandatory evacuations, because there was no way to force people to abandon their homes. "I can't go door to door," he explained. In Mississippi, Gov. Haley Barbour (R) told his wife he was worried about hurricane fatigue; after a series of false alarms along the Gulf Coast, the evacuation routine was starting to get old.

But local officials got the word out that this was no ordinary storm, and residents took them seriously, streaming out of town in the contra-flow lanes. Hurricane Pam's leaders had predicted a 65 percent evacuation rate, but Maestri reported 70 percent in Jefferson Parish, thanks in part to a church buddy program that provided rides for as many as 25,000 residents, and St. Bernard Parish reported 90 percent. "We had some hard-headed sons of bitches who wouldn't leave, but we made sure everyone knew this was the one," said emergency manager Larry Ingargiola.

Nearly a month into his five-week vacation near Crawford, Tex., the president first mentioned the storm in a meeting with aides that afternoon. It's possible, he told senior adviser Dan Bartlett, that he would have to scrap a planned event the following Thursday to talk about identity theft, and would add a trip to the Gulf Coast instead. When Blanco asked Bush to declare a federal emergency in Louisiana that day, Bush readily agreed.

The president was told the evacuation was proceeding as planned for New Orleans, according to a senior White House official, and that 11,000 National Guard troops would end up in a position to respond. But Lt. Gen. H. Steven Blum, chief of the Guard, said there were only about 5,100 members on duty in Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama before landfall.

At 1:30 p.m. on Saturday, Mayor Ray Nagin and Blanco held a news conference to urge New Orleans residents to make arrangements to evacuate. "This is not a test," the mayor said. "This is the real deal."

Nagin said that by daybreak, he might have to order the first mandatory evacuation in New Orleans history, although his staff was still checking whether that would pose liability problems for the city. Nagin did not tell everyone to leave immediately, because the regional plan called for the suburbs to empty out first, but he did urge residents in particularly low-lying areas to "start moving -- right now, as a matter of fact." He said the Superdome would be open as a shelter of last resort, but essentially he told tourists stranded in the Big Easy that they were out of luck.

"The only thing I can say to them is I hope they have a hotel room, and it's a least on the third floor and up," Nagin said. "Unfortunately, unless they can rent a car to get out of town, which I doubt they can at this point, they're probably in the position of riding the storm out."

In fact, while the last regularly scheduled train out of town had left a few hours earlier, Amtrak had decided to run a "dead-head" train that evening to move equipment out of the city. It was headed for high ground in Macomb, Miss., and it had room for several hundred passengers. "We offered the city the opportunity to take evacuees out of harm's way," said Amtrak spokesman Cliff Black. "The city declined."

So the ghost train left New Orleans at 8:30 p.m., with no passengers on board.

That night, Mayfield picked up his phone again, to make sure Govs. Blanco and Barbour understood the potential for disaster. "I wanted to be able to go to sleep that night," he said. He told Barbour that Katrina had the potential to be a "Camille-like storm," referring to the August 1969 hurricane with 200-mph winds, and warned Blanco that this one would be a "big, big deal." Blanco was still unsure that Nagin fully understood, and urged Mayfield to call him personally.

"I told him, 'This is going to be a defining moment for a lot of people,' " Mayfield recalled.

Sunday, Aug. 28

'We sat here for five days waiting. Nothing!'

"We're facing the storm most of us have feared," Nagin told an early-morning news conference, the governor at his side. Katrina was now a Category 5 hurricane, set to make landfall overnight.

Minutes earlier, Blanco had been pulled out to take a call from the president, pressed into service by FEMA's Brown to urge a mandatory evacuation. Blanco told him that's just what the mayor would order.

Nagin also announced that the city had set up 10 refuges of last resort, and promised that public buses would pick up stragglers in a dozen locations to take them to the Superdome and other shelters.

But he never mentioned the numbers that had haunted experts for years, the estimated 100,000 city residents without their own transportation. And he never mentioned that the state's comprehensive disaster plan, written in 2000 and posted on a state Web site, called for buses to take people out of the city once the governor declared a state of emergency.

In reality, Nagin's advisers never intended to follow that plan -- and knew many residents would stay behind. "We always knew we did not have the means to evacuate the city," said Terry Ebbert, the sharp-tongued city director of emergency management.

At 10 a.m., in case there were still any doubters, the National Weather Service issued a hurricane warning with apocalyptic predictions: "Most of the area will be uninhabitable for weeks, perhaps longer . . . At least one-half of well-constructed homes will have roof and wall failure. . . . Water shortages will make human suffering incredible by modern standards."

Not long after that forecast, Bush joined the daily FEMA videoconference from his Texas ranch, as a series of briefers sketched out scenarios of destruction. "We were expecting something awful," recalled Maj. Gen. Don T. Riley of the Army Corps.

Many state officials on the call feared there simply wouldn't be enough help to go around once the storm cleared, and peppered FEMA with questions about resources. "We were concerned about making sure there were enough commodities to cover all three states, water, ice, MREs," recalled Bruce Baughman, Alabama's top emergency adviser.

At that point, FEMA had already stockpiled for immediate distribution 2.7 million liters of water, 1.3 million meals ready to eat and 17 million pounds of ice, a Department of Homeland Security official said. But Louisiana received a relatively small portion of the supplies; for example, Alabama got more than five times as much water for distribution. "It was what they would move for a normal hurricane -- business as usual versus a superstorm," concluded Mark Ghilarducci, a former FEMA official now working as a consultant for Blanco.

By late Sunday, as millions of people in the Gulf region sought a safe place to hunker down, hundreds of shelter beds upstate lay empty. "We could have taken a lot more," said Joe Becker, senior vice president for preparedness and response at the Red Cross. "The problem was transportation." The New Orleans plan for public buses that would take people upstate was never implemented, and while many residents did manage to get out of town -- about 80 percent, the mayor said -- tens of thousands did not.

"Once a mandatory evacuation was ordered, those buses should have been leaving those parishes with those people on them," said Chip Johnson, chief of emergency operations in Avoyelles Parish, who helped put together the plan. In Avoyelles alone, there was room for at least 200 or 300 more on Sunday night before the storm, and more shelters could have opened if necessary. "I don't know why that didn't happen."

At the Superdome, city officials reckoned that 9,000 people had arrived by evening to ride out the storm. FEMA had sent seven trailers full of food and water -- enough, it estimated, to supply two days of food for as many as 22,000 people and three days of water for 30,000. Ebbert said he knew conditions in the Superdome would be "horrible," but Hurricane Pam had predicted a massive federal response within two days, and Ebbert said the city's plan was to "hang in there for 48 hours and wait for the cavalry."

Around midnight, at the last of the day's many conference calls, local officials ticked off their final requests for FEMA and the state. Maestri specifically asked for medical units, mortuary units, ice, water, power and National Guard troops.

"We laid it all out," he recalled. "And then we sat here for five days waiting. Nothing!"

Monday, Aug. 29

'We need everything you've got.'

Hurricane Katrina made landfall in Louisiana around 6 a.m. Central time, and within an hour, New Orleans Mayor Nagin was hearing reports of water breaking through his city's levees. At 8:14 a.m., the National Weather Service reported a levee breach along the Industrial Canal, and warned that the Ninth Ward was likely to experience extremely severe flooding. A protective floodwall along Lake Pontchartrain had given way as well, which meant that billions of gallons of water were draining into the city.

This was the worst of the worst-case scenarios. New Orleans is a soup bowl of a city, most of it well below sea level; everyone knew a serious crevasse could fill it with 20 feet of water. Even the gloomy Hurricane Pam drill had optimistically assumed the levees would hold, but they were designed to withstand only a Category 3 storm, and Katrina created at least five breaches at three locations. Now the waters were rising.

And nobody in charge seemed to know it.

On Saturday, according to Army Corps homeland security chief Ed Hecker, the corps had warned FEMA that Katrina would probably send water over the levees, and quite possibly breach them. On Sunday, the Army Corps's Riley had told the FEMA videoconference that a plan was in place to repair levee damage once the storm passed.

But now the power was out, roads were unnavigable, and communication was practically nonexistent; even Nagin's aides had to "loot" an Office Depot for equipment to install Internet phone service. Maj. Gen. Bennett C. Landreneau, the top National Guard official in Louisiana, found his New Orleans barracks under 20 feet of water; vehicles were washed out, and troops had to take refuge upstairs.

The federal disaster response plan hinges on transportation and communication, but National Guard officials in Louisiana and Mississippi had no contingency plan if they were disrupted; they had only one satellite phone for the entire Mississippi coast, because the others were in Iraq. The New Orleans police managed to notify the corps that the 17th Street floodwall near Lake Pontchartrain had busted, and Col. Richard Wagenaar, the top corps official in New Orleans, tried to drive to the site to check it out. But he couldn't get through because of high water, trees and other obstacles on the road.

In St. Bernard Parish, a hardscrabble industrial zone just outside New Orleans, emergency manager Ingargiola realized that his entire community was marooned. He did not even have contact with his own emergency shelter, so he didn't know its roof had blown off. But local officials immediately launched rescue efforts with boats they had prepared in advance. They figured help was on the way.

At 11 a.m., ABC News reported that some New Orleans levees had been breached, and a few other outlets broadcast similarly sketchy reports that day. But most of the early coverage suggested that New Orleans had dodged a bullet as Katrina's strongest gusts had passed east of the city. Wagenaar finally confirmed the levee breaches during an overflight that evening, but his agency's first post-Katrina news release boasted about the performance of its infrastructure: "The fact that Katrina didn't cause more damage is a testament to the structural integrity of the hurricane levee protection system."

At the White House, one official recalled, "there was a general sigh of relief." On a trip to Arizona, the president shared a birthday cake with Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), who was turning 69. During a speech about the Medicare drug plan, Bush noted that he had just spoken to Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff -- about immigration.

The federal interagency team seemed to recognize the urgency of the crisis at a meeting that morning, discussing the potential for six months of flooding in New Orleans, and a preliminary Department of Energy conclusion that as many as 2,000 of 6,500 oil and gas platforms in the Gulf could be affected. But before noon, FEMA's Brown sent a remarkably mild memo to Chertoff, politely requesting 1,000 employees to be ready to head south "within 48 hours." Brown's memo suggested that recruits bring mosquito repellent, sunscreen and cash, because "ATMs may not be working."

"Thank you for your consideration in helping us meet our responsibilities in this near catastrophic event," Brown concluded.

At the U.S. military's Northern Command, officers had been watching the storm since early in the week and had started sending Army brigade commanders and their staffs to the three affected Gulf states by Thursday. "We were all watching the evacuation," Maj. Gen. Richard Rowe, Northcom's top operations officer, recalled. "We knew that it would be among the worst storms ever to hit the United States." But on Monday, the only request the U.S. military received from FEMA was for a half-dozen helicopters.

As water poured into the city, as many as 20,000 more residents poured into the Superdome. "People started coming out of the woodwork," Ebbert said. The stadium was hot and fetid, and tempers were flaring. Ebbert said he told FEMA that night that the city would need buses to evacuate 30,000 people. "It just took a long time," he said.

State officials managed to get 60 boats to New Orleans for search-and-rescue operations by Monday night. By daybreak Tuesday, the state would have an additional 150 boats on the hunt. "We were very convinced that this thing was going to be a catastrophic event," said Bennett Landreneau, who was coordinating the state's rescue operations.

Around 6 p.m., as Governor Blanco was about to hold a news conference in Baton Rouge to discuss the damage, Blanco's communications director whispered that the president was on the line. The governor returned to a windowless office in her situation room and pleaded with the president for assistance.

"We need your help," she said. "We need everything you've got."

Tuesday, Aug. 30

'I've got a sewage problem that's going to be a medical disaster.'

Over the weekend, Texas emergency chief Jack Colley had continued to fret that the forecasts would turn out wrong and Katrina would pummel his state. "Don't worry," the hurricane center's Mayfield had assured him, "Texas is going to sit this one out." But now, it turned out, the storm was coming to Texas in another form. At 2:45 a.m., Louisiana's secretary of state for social services woke up Colley at home.

"Can you accept 25,000 people?" she asked.

Colley thought of his state's designated refuge: the Astrodome. Yes, he said. By 6 a.m., Colley's team was preparing to send Texas state troopers to escort the fleet of buses they had been assured would come soon. But they didn't know how many buses, or when, "and there were no answers that anyone could provide," said Steve McCraw, the homeland security adviser to Texas Gov. Rick Perry (R). Blanco ordered the Superdome evacuated, but Col. Jeff Smith, Louisiana's emergency preparedness chief, grew frustrated at FEMA's inability to send buses to move people out. "We'd call and say: 'Where are the buses?' " he recalled, shaking his head. "They have a tracking system and they'd say: 'We sent 349.' But we didn't see them."

By 5 a.m., Bush had already been briefed about New Orleans's rising waters, and decided that he would cut short his vacation the next day. Later that morning, the interagency group urgently commissioned new damage assessments, and local officials warned that the scale of the coastal damage could be "too extensive to calculate or summarize." Nagin declared that 80 percent of his city was underwater; after flying over New Orleans with FEMA's Brown and witnessing the widespread flooding, Blanco announced that "the devastation is greater than our worst fears."

But in public, Brown and Chertoff gave no such indication of the cataclysm, later saying they were not told until midday that the levee breaches were irreparable and would flood the city. William Lokey, FEMA's coordinator on the ground, declared that morning: "I don't want to alarm everybody that New Orleans is filling up like a bowl. That is just not happening."

That was exactly what was happening, and many state and local officials quickly concluded that the federal bureaucracy was spinning its wheels.

At the noon videoconference, several participants said, Louisiana's Smith heatedly demanded federal help. Where were the buses? At first, Smith recalled, he had asked for 450 buses, then 150 more, then an additional 500; by the end of the day, none had arrived. The first evacuees did not arrive at the Astrodome until 10 p.m. Wednesday -- on a school bus commandeered by a resourceful 20-year-old.

In Jefferson Parish, Maestri sent out an urgent call that morning for power packs in hopes of rescuing his county's faltering sewage system. "In Pam, they had said they'd have those ready on pallets so they could airlift them in, no problem," he later recalled. "It's 11 days later, and I still don't have them. I've got a sewage problem that's going to be a medical disaster like we've never seen in this country. Where's the cavalry?"

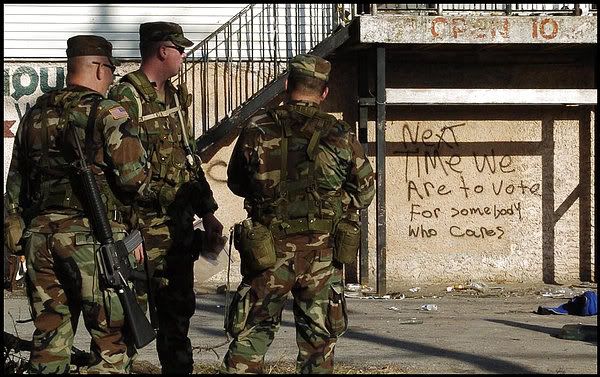

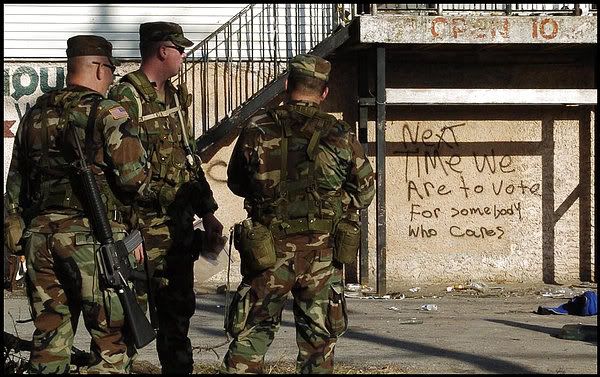

In the drowning city, chaos erupted. Looting was widespread, sometimes in full view of outnumbered police and often unarmed National Guard troops. Hundreds of New Orleans police officers quit. Others performed their duties courageously, and so did many state and federal personnel, but for now they focused on rescue and recovery. In general, the cavalry was nowhere to be seen, and everyone seemed to know it.

"As systems either were not followed or broke down, people just went to what they believed they could handle. Every man for himself," said Ghilarducci, Blanco's adviser. "You don't use the system, you don't use resources effectively and it breaks down."

The U.S. military command charged with domestic safekeeping was watching wild images from New Orleans. On their own initiative, Rowe said, Northcom staff members broached the idea of sending active-duty ground troops. They wanted to take a force of 3,000 soldiers designated to respond to a nuclear, chemical or biological attack, strip out unneeded elements such as chemical decontamination teams and send them to the Gulf Coast.

At this point, Blanco believed she had long since asked for the maximum possible help from the federal government. But the military was not specifically asked for its assistance. Blum began moving National Guard forces into the area before he was asked, but they had trouble navigating through a modern-day Atlantis.

Army Corps officials were trying to close the gaps in the levees, but their hurried efforts to stem the flow were hampered by a lack of supplies. They could not find 10-ton sandbags or the slings they needed to drop the bags from helicopters; most of their personnel had evacuated, and so had their local contractors. "We didn't expect any breaches," Dan Hitchings of the agency's Mississippi Valley Division later explained. "We didn't think we were going to have a wall down." The corps tried to drop smaller sandbags into the 17th Street breach, but they simply floated away with the current.

FEMA managed to deliver 65,000 meals to the Superdome, but by the end of the day, water was rising so fast that the agency was unable to unload five more truckloads of food and water. That evening, in a belated bow to televised reality, Chertoff declared the unfolding disaster an "incident of national significance," triggering the government's highest level of response for the first time since the new post-9/11 system had been designed. He did not publicly announce the move until the next day.

Wednesday, Aug. 31

'They didn't have a full sense of what they were dealing with.'

Dawn found a handful of buses outside the Superdome, and an estimated 23,000 people clamoring for a ride. FEMA had promised hundreds of buses, but they were arriving, Louisiana's Smith recalled, "in a trickle." And unbeknownst to FEMA, a new circle of hell was opening downtown, as the New Orleans convention center filled with an estimated 25,000 evacuees, many of them unable to get to the flooded area around the Superdome. There was no food, no water and no feds. A spree of robbery, looting and gunfire erupted inside as police dispatched to the center stayed almost exclusively on the perimeter, according to police and witnesses, outnumbered and unable to quell the mayhem.

New Orleans as a city had all but ceased to exist. Nagin spoke of "thousands" dead. Blanco publicly pleaded for 40,000 National Guard troops. In a conference call with Guard officials in the region, Blum asked if they had what they needed. They said no.

"They said that this is bigger than anything we've ever seen or imagined," Blum recalled. "This had touched them personally. Even at that time they didn't have a full sense of what they were dealing with." Blum immediately arranged a videoconference with every adjutant general around the country, and 3,000 Guard troops streamed into New Orleans over the next 24 hours, enough to replace the entire city police force. By Saturday, the Guard would have 30,000 troops in the region.

Bush, winging his way back from vacation, paused to swoop low over the prostrate city on Air Force One. Back in Washington, he convened a stunned Cabinet.

Bush came in with a "sense of urgency in his tone" after his aerial tour, recalled Mike Leavitt, the secretary of health and human services. "It was, 'Has anybody thought of that, who's doing this? I want you to do this and this and this.' " But the scale of the problem seemed inexplicably massive, and the plans they drew up that day would take agonizing days to carry out. Leavitt, for example, declared a federal health emergency throughout the Gulf Coast, calling for 2,500 additional hospital beds in the region by Friday, and another 2,500 in the 72 hours after that. "We had to scramble the jets," he said.

At the interagency coordination meetings, gargantuan new proposals were being discussed, such as housing the estimated million-plus newly homeless in tent cities, mobile home parks and even federalized cruise ships. At Northcom, officials were still waiting for a call requesting active-duty troops. The Navy dispatched three aid ships from Norfolk; they were due to arrive Sept. 4.

But assistance that was available was often blocked. In the Gulf, not 100 miles away from New Orleans, sat the 844-foot USS Bataan, equipped with six operating rooms and beds for 600 patients. Starting Wednesday, Amtrak offered to run a twice-a-day shuttle for as many as 600 evacuees from a rail yard west of New Orleans to Lafayette, La. The first run was not organized until Saturday. Officials then told Amtrak they would not require any more trains.

Out of public view, the White House was considering an outright federal takeover of the emergency efforts, escalating a partisan feud with the Democratic governor as Bush aides questioned her ability to manage the crisis. Despite days of pleading, the White House argued that her plea for more troops had come in only at 7:21 that morning. Amid the reports of looting and general lawlessness, the White House instructed lawyers in the Justice Department and other agencies to investigate invoking the Insurrection Act, last used during the 1992 Los Angeles riots.

But a fierce debate erupted, said an administration official who participated in the meetings and who spoke on the condition of anonymity, centering on whether Bush could order a federal takeover of the relief effort with or without Blanco's approval. White House Chief of Staff Andrew H. Card Jr., recalled from his Maine vacation, broached the question with Blanco, a senior White House official said. Later, the president called from the Oval Office to press the same idea. Both times, Blanco balked.

But her aides said she had no reason to believe the federal government would start rising to the occasion. They also said that the president never asked her directly about federalizing the state's troops. "We wouldn't have turned down federal troops," one Blanco aide said. "We were asking for them."

Thursday, Sept. 1

'They didn't hear from me . . . and they didn't come to look.'

At 4 a.m., 550 tired, hungry, frightened evacuees from the Superdome filed into Houston's Astrodome. Soon there would be thousands. Now, Houston had to figure out how to absorb not 25,000 but as many as 250,000 Louisianans.

Within hours, it was clear that many of the evacuees required urgent medical care, including 50 children from a hospital and helicopters full of soaking-wet adults.

And while initial plans had called for sheltering the entire evacuation at the Astrodome, "we found out that while you could put 23,000 people in the Dome, you wouldn't want to," as Harris County Judge Robert Eckels recalled. By evening, buses were being sent elsewhere.

Meanwhile, St. Bernard Parish was still marooned. Out of 28,000 structures in the parish, only 52 were undamaged, and as many as 5,000 were simply gone. Every day since the storm, Ingargiola had waited for the federal government to bring food, water, electricity, anything. "They didn't hear from me for four days, and they didn't come to look for us," Ingargiola recalled. "Did they think we were okay?"

Anger was also rising at federal officials, who often seemed to be getting in the way. At Louis Armstrong International Airport, commercial airlines had been flying in supplies and taking out evacuees since Monday. But on Thursday, after FEMA took over the evacuation, aviation director Roy A. Williams complained that "we are packed with evacuees and the planes are not being loaded and there are gaps of two or three hours when no planes are arriving." Eventually, he started fielding "calls from airlines saying, 'Well, we are being told by FEMA that you don't need any planes.' And of course we need planes. I had thousands of people on the concourses."

At the convention center, thousands had gathered by Thursday without supplies. There were no buses and none on the way. Nagin, almost in tears, issued a "desperate SOS."

But official Washington seemed not to be watching the televised chaos. Bush was still insisting the storm and catastrophic flooding his own government had foretold was a surprise. "I don't think anyone anticipated the breach of the levees," he said.

Later, in another television interview, Brown insisted that everything was "under control." And though the crowds had started to flock to the convention center two days earlier, Brown said: "We learned about the convention center today."

In private, Bush had reached a "tipping point" Thursday, a senior aide said, when he watched images from the convention center. But the debate inside his administration still raged over whether to federalize the Guard and take overall control of New Orleans.

At Northcom, they were still awaiting orders. That day, Rowe said, the planners had come up with another military option -- a logistical force to back up the overtaxed relief effort on the ground. The idea was to send as many as 1,500 troops each to Louisiana and Mississippi. At Fort Bragg, N.C., the 82nd Airborne was on standby to deploy, so was the First Cavalry Division at Fort Hood, Tex., and Marine bases on both coasts.

Bush discussed the idea with Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld that day, but still held back on deciding. The cavalry would have to wait.

Friday, Sept. 2

'The results are not acceptable.'

At 7 a.m., Bush called his generals to the White House, along with Rumsfeld and Chertoff. They discussed final terms of Bush's plan -- by nightfall, he would demand that Blanco hand over control of National Guard troops. And they hashed out the idea of sending in the active-duty military, though troops from the 82nd Airborne and 1st Cavalry would not get their orders until the next day.

Then Bush left for the stricken region.

Before boarding his helicopter, the president had a terse comment about his government's performance. "The results are not acceptable." But shortly after they touched down in Alabama, the president's tone changed. He turned to Brown, the focus of much of the criticism from state and local officials, and declared: "Brownie, you're doing a heck of a job."

Later in the tour, Homeland Security Secretary Chertoff visited Jefferson Parish, and told Maestri he was doing a wonderful job. "Where are the resources?" Maestri asked.

"He said: 'It's coming, it's coming,' " Maestri recalled. "Yeah, well, Christmas is coming, too." [Susan B. Glasser and Michael Grunwald The Washington Post]

Walter Maestri had dreaded this call for a decade, ever since he took over emergency management for Jefferson Parish, a marshy collection of suburbs around New Orleans. It was Friday night, Aug. 26, and his friend Max Mayfield was on the line. Mayfield is the head of the National Hurricane Center, and he wasn't calling to chat.

"Walter," Mayfield said, "get ready."

"What do you mean?" Maestri asked, though he already knew the answer.

Hurricane Katrina had barreled into the Gulf of Mexico, and Mayfield's latest forecast had it smashing into New Orleans as a Category 4 or 5 storm Monday morning. Maestri already had 10,000 body bags in his parish, in case he ever got a call like this.

"This could be the one," Mayfield told him.

Maestri heard himself gasp: "Oh, my God."

In July 2004, Maestri had participated in an exercise called Hurricane Pam, a simulation of a Category 3 storm drowning New Orleans. Emergency planners had concluded that a real Pam would create a flood of unimaginable proportions, killing tens of thousands of people, wiping out hundreds of thousands of homes, shutting down southeast Louisiana for months.

The practice run for a New Orleans apocalypse had been commissioned by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the federal government's designated disaster shop. But the funding ran out and the doomsday scenario became just another prescient -- but buried -- government report. Now, practice was over.

And Pam's lessons had not been learned.

As the floodwaters recede and the dead are counted, what went wrong during a terrible week that would render a modern American metropolis of nearly half a million people uninhabitable and set off the largest exodus of people since the Civil War, is starting to become clear. Federal, state and local officials failed to heed forecasts of disaster from hurricane experts. Evacuation plans, never practical, were scrapped entirely for New Orleans's poorest and least able. And once floodwaters rose, as had been long predicted, the rescue teams, medical personnel and emergency power necessary to fight back were nowhere to be found.

Compounding the natural catastrophe was a man-made one: the inability of the federal, state and local governments to work together in the face of a disaster long foretold.

In many cases, resources that were available were not used, whether Amtrak trains that could have taken evacuees to safety before the storm or the U.S. military's 82nd Airborne division, which spent days on standby waiting for orders that never came. Communications were so impossible the Army Corps of Engineers was unable to inform the rest of the government for crucial hours that levees in New Orleans had been breached.

The massive rescue effort that resulted was a fugue of improvisation, by fleets of small boats that set sail off highway underpasses and angry airport directors and daredevil helicopter pilots. Tens of thousands were saved as the city swamped; they were plucked from rooftops and bused, eventually, out of the disaster zone.

But it was an infuriating time of challenge when government seemed unable to meet its basic compact with its citizens. After the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, an entirely new Department of Homeland Security had been created, charged with doing better the next time, whether the crisis was another terrorist attack or not. Its new plan for safeguarding the nation, unveiled just this year, clearly spelled out the need to take charge in assisting state and local governments sure to be "overwhelmed" by a cataclysmic event.

Instead, confusion reigned at every level of officialdom, according to dozens of interviews with participants in Louisiana, Mississippi and Washington. "No one had access. . . . No one had communication. . . . Nobody knew where the people were," recalled Secretary of Health and Human Services Mike Leavitt, whose department did not declare the Gulf Coast a public health emergency until two days after the storm.

Despite pleas by Bush administration officials to refrain from "the blame game," mutual recriminations among officeholders began even before New Orleans's trapped residents had been rescued. The White House secretly debated federalizing authority in a city under the control of a Democratic mayor and governor, and critics in both parties assailed FEMA and raised questions about President Bush.

That Friday, as Maestri prepared for the Big One, he had known that his region's survival would depend on the federal response. After Hurricane Pam, FEMA officials had concluded that local authorities might be on their own for 48 or even 60 hours after a real storm, but they had assured Maestri that the cavalry would swoop in after that, and take care of the region's needs.

"Like a fool, I believed them," Maestri said last week.

Friday, Aug. 26

'Why aren't we treating this as a bigger emergency?'

At 5 a.m., Hurricane Katrina entered the Gulf of Mexico with the Louisiana coastline in its sights. In Elmwood, La., dozens of federal, state and local disaster officials were meeting to discuss storm response, but their topic was Tropical Storm Cindy, which had come ashore on July 5. While leaders of Louisiana's Office of Homeland Security and the National Guard tracked Katrina with a handheld device, local emergency managers learned how they could submit claims for Cindy's relatively modest damage.

"Shouldn't we just apply for Katrina money now?" quipped Jim Baker, operations superintendent for the East Jefferson Levee District.

As the storm track hooked toward New Orleans, the disaster officials began passing the handheld device around the room. It was becoming clear that Katrina was no joking matter. But it was already getting late to be getting serious.

After the Hurricane Pam drill, disaster planners had concluded that evacuating New Orleans could take as long as 72 hours before a storm's landfall. By midday Friday, it was 66 hours before Katrina would end up hitting, and the threat was just starting to sink in. "With this storm, people should have evacuated no later than Friday," said a senior official in a neighboring state. "Anything after that was very risky."

In Washington, the cumbersome machinery of catastrophe began to crank up.

At the Department of Homeland Security, the 180,000-employee bureaucracy created after the Sept. 11 attacks, that meant convening the Interagency Incident Management Group. About 20 federal agencies had seats at the table, from the State Department to the Veterans Affairs Department.

FEMA was still the lead disaster agency, as it had been since 1979, but was now just a piece of DHS. Instead of Cabinet-level status and a direct line to the president, its director -- Michael D. Brown, a lawyer and former Arabian horse association official -- was an undersecretary. Funding had been cut over the past four years for FEMA's disaster-relief mission, and experienced personnel had left in droves. While experts who closely tracked FEMA had publicly fretted about the agency's reduced status, their warnings had not received widespread public attention.

By Friday, FEMA's emergency headquarters for Katrina was already running; technically, the agency was at level one, its highest level of alert.

But as the headquarters staff came in, there was a strange sense of inaction, as if "nobody's turning the key to start the engine," said one team leader, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. For his group, Friday was a day to sit around wondering, "Why aren't we treating this as a bigger emergency? Why aren't we doing anything?"

That evening, shortly before Max Mayfield made his call to Walter Maestri, Louisiana Gov. Kathleen Babineaux Blanco (D) declared a state of emergency.

Saturday, Aug. 27

'This is not a test: This is the real deal.'

By morning, Katrina was already a Category 3 hurricane, and Mayfield was predicting it could make landfall near New Orleans as an even deadlier Category 4. On FEMA's daily noon videoconference, he looked around the U-shaped conference table in Washington and saw a lot of newcomers to the disaster world among the agency's political appointees. But he knew many of the professionals listening in from the Gulf states had been through his hurricane prep course. They knew this was no drill.

"The emergency guys, they know what a Cat 4 is," Mayfield recalled. And this had the potential to be a Category 5, only the fourth in U.S. history. "This one is different," Mayfield told the videoconference. "It's strong, but it's also much, much larger."

When talk turned to New Orleans, Mayfield mentioned the possibility of water overwhelming the levees; his center soon forecast a storm surge as high as 25 feet, far above the 17-foot clearance for most of the city's storm protection. "Clearly on Saturday, we knew it was going to be the Big One," recalled Jack Colley, Texas's veteran disaster man. "We were very convinced this was going to be a very catastrophic event."

The challenge was to get people out of harm's way. All day long, Louisiana officials announced voluntary evacuations, and Blanco implemented a "contra-flow" traffic plan to help as coastal residents reach higher grounds. Maestri said there was no point in ordering mandatory evacuations, because there was no way to force people to abandon their homes. "I can't go door to door," he explained. In Mississippi, Gov. Haley Barbour (R) told his wife he was worried about hurricane fatigue; after a series of false alarms along the Gulf Coast, the evacuation routine was starting to get old.

But local officials got the word out that this was no ordinary storm, and residents took them seriously, streaming out of town in the contra-flow lanes. Hurricane Pam's leaders had predicted a 65 percent evacuation rate, but Maestri reported 70 percent in Jefferson Parish, thanks in part to a church buddy program that provided rides for as many as 25,000 residents, and St. Bernard Parish reported 90 percent. "We had some hard-headed sons of bitches who wouldn't leave, but we made sure everyone knew this was the one," said emergency manager Larry Ingargiola.

Nearly a month into his five-week vacation near Crawford, Tex., the president first mentioned the storm in a meeting with aides that afternoon. It's possible, he told senior adviser Dan Bartlett, that he would have to scrap a planned event the following Thursday to talk about identity theft, and would add a trip to the Gulf Coast instead. When Blanco asked Bush to declare a federal emergency in Louisiana that day, Bush readily agreed.

The president was told the evacuation was proceeding as planned for New Orleans, according to a senior White House official, and that 11,000 National Guard troops would end up in a position to respond. But Lt. Gen. H. Steven Blum, chief of the Guard, said there were only about 5,100 members on duty in Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama before landfall.

At 1:30 p.m. on Saturday, Mayor Ray Nagin and Blanco held a news conference to urge New Orleans residents to make arrangements to evacuate. "This is not a test," the mayor said. "This is the real deal."

Nagin said that by daybreak, he might have to order the first mandatory evacuation in New Orleans history, although his staff was still checking whether that would pose liability problems for the city. Nagin did not tell everyone to leave immediately, because the regional plan called for the suburbs to empty out first, but he did urge residents in particularly low-lying areas to "start moving -- right now, as a matter of fact." He said the Superdome would be open as a shelter of last resort, but essentially he told tourists stranded in the Big Easy that they were out of luck.

"The only thing I can say to them is I hope they have a hotel room, and it's a least on the third floor and up," Nagin said. "Unfortunately, unless they can rent a car to get out of town, which I doubt they can at this point, they're probably in the position of riding the storm out."

In fact, while the last regularly scheduled train out of town had left a few hours earlier, Amtrak had decided to run a "dead-head" train that evening to move equipment out of the city. It was headed for high ground in Macomb, Miss., and it had room for several hundred passengers. "We offered the city the opportunity to take evacuees out of harm's way," said Amtrak spokesman Cliff Black. "The city declined."

So the ghost train left New Orleans at 8:30 p.m., with no passengers on board.

That night, Mayfield picked up his phone again, to make sure Govs. Blanco and Barbour understood the potential for disaster. "I wanted to be able to go to sleep that night," he said. He told Barbour that Katrina had the potential to be a "Camille-like storm," referring to the August 1969 hurricane with 200-mph winds, and warned Blanco that this one would be a "big, big deal." Blanco was still unsure that Nagin fully understood, and urged Mayfield to call him personally.

"I told him, 'This is going to be a defining moment for a lot of people,' " Mayfield recalled.

Sunday, Aug. 28

'We sat here for five days waiting. Nothing!'

"We're facing the storm most of us have feared," Nagin told an early-morning news conference, the governor at his side. Katrina was now a Category 5 hurricane, set to make landfall overnight.

Minutes earlier, Blanco had been pulled out to take a call from the president, pressed into service by FEMA's Brown to urge a mandatory evacuation. Blanco told him that's just what the mayor would order.

Nagin also announced that the city had set up 10 refuges of last resort, and promised that public buses would pick up stragglers in a dozen locations to take them to the Superdome and other shelters.

But he never mentioned the numbers that had haunted experts for years, the estimated 100,000 city residents without their own transportation. And he never mentioned that the state's comprehensive disaster plan, written in 2000 and posted on a state Web site, called for buses to take people out of the city once the governor declared a state of emergency.

In reality, Nagin's advisers never intended to follow that plan -- and knew many residents would stay behind. "We always knew we did not have the means to evacuate the city," said Terry Ebbert, the sharp-tongued city director of emergency management.

At 10 a.m., in case there were still any doubters, the National Weather Service issued a hurricane warning with apocalyptic predictions: "Most of the area will be uninhabitable for weeks, perhaps longer . . . At least one-half of well-constructed homes will have roof and wall failure. . . . Water shortages will make human suffering incredible by modern standards."

Not long after that forecast, Bush joined the daily FEMA videoconference from his Texas ranch, as a series of briefers sketched out scenarios of destruction. "We were expecting something awful," recalled Maj. Gen. Don T. Riley of the Army Corps.

Many state officials on the call feared there simply wouldn't be enough help to go around once the storm cleared, and peppered FEMA with questions about resources. "We were concerned about making sure there were enough commodities to cover all three states, water, ice, MREs," recalled Bruce Baughman, Alabama's top emergency adviser.

At that point, FEMA had already stockpiled for immediate distribution 2.7 million liters of water, 1.3 million meals ready to eat and 17 million pounds of ice, a Department of Homeland Security official said. But Louisiana received a relatively small portion of the supplies; for example, Alabama got more than five times as much water for distribution. "It was what they would move for a normal hurricane -- business as usual versus a superstorm," concluded Mark Ghilarducci, a former FEMA official now working as a consultant for Blanco.

By late Sunday, as millions of people in the Gulf region sought a safe place to hunker down, hundreds of shelter beds upstate lay empty. "We could have taken a lot more," said Joe Becker, senior vice president for preparedness and response at the Red Cross. "The problem was transportation." The New Orleans plan for public buses that would take people upstate was never implemented, and while many residents did manage to get out of town -- about 80 percent, the mayor said -- tens of thousands did not.

"Once a mandatory evacuation was ordered, those buses should have been leaving those parishes with those people on them," said Chip Johnson, chief of emergency operations in Avoyelles Parish, who helped put together the plan. In Avoyelles alone, there was room for at least 200 or 300 more on Sunday night before the storm, and more shelters could have opened if necessary. "I don't know why that didn't happen."

At the Superdome, city officials reckoned that 9,000 people had arrived by evening to ride out the storm. FEMA had sent seven trailers full of food and water -- enough, it estimated, to supply two days of food for as many as 22,000 people and three days of water for 30,000. Ebbert said he knew conditions in the Superdome would be "horrible," but Hurricane Pam had predicted a massive federal response within two days, and Ebbert said the city's plan was to "hang in there for 48 hours and wait for the cavalry."

Around midnight, at the last of the day's many conference calls, local officials ticked off their final requests for FEMA and the state. Maestri specifically asked for medical units, mortuary units, ice, water, power and National Guard troops.

"We laid it all out," he recalled. "And then we sat here for five days waiting. Nothing!"

Monday, Aug. 29

'We need everything you've got.'

Hurricane Katrina made landfall in Louisiana around 6 a.m. Central time, and within an hour, New Orleans Mayor Nagin was hearing reports of water breaking through his city's levees. At 8:14 a.m., the National Weather Service reported a levee breach along the Industrial Canal, and warned that the Ninth Ward was likely to experience extremely severe flooding. A protective floodwall along Lake Pontchartrain had given way as well, which meant that billions of gallons of water were draining into the city.

This was the worst of the worst-case scenarios. New Orleans is a soup bowl of a city, most of it well below sea level; everyone knew a serious crevasse could fill it with 20 feet of water. Even the gloomy Hurricane Pam drill had optimistically assumed the levees would hold, but they were designed to withstand only a Category 3 storm, and Katrina created at least five breaches at three locations. Now the waters were rising.

And nobody in charge seemed to know it.

On Saturday, according to Army Corps homeland security chief Ed Hecker, the corps had warned FEMA that Katrina would probably send water over the levees, and quite possibly breach them. On Sunday, the Army Corps's Riley had told the FEMA videoconference that a plan was in place to repair levee damage once the storm passed.

But now the power was out, roads were unnavigable, and communication was practically nonexistent; even Nagin's aides had to "loot" an Office Depot for equipment to install Internet phone service. Maj. Gen. Bennett C. Landreneau, the top National Guard official in Louisiana, found his New Orleans barracks under 20 feet of water; vehicles were washed out, and troops had to take refuge upstairs.

The federal disaster response plan hinges on transportation and communication, but National Guard officials in Louisiana and Mississippi had no contingency plan if they were disrupted; they had only one satellite phone for the entire Mississippi coast, because the others were in Iraq. The New Orleans police managed to notify the corps that the 17th Street floodwall near Lake Pontchartrain had busted, and Col. Richard Wagenaar, the top corps official in New Orleans, tried to drive to the site to check it out. But he couldn't get through because of high water, trees and other obstacles on the road.

In St. Bernard Parish, a hardscrabble industrial zone just outside New Orleans, emergency manager Ingargiola realized that his entire community was marooned. He did not even have contact with his own emergency shelter, so he didn't know its roof had blown off. But local officials immediately launched rescue efforts with boats they had prepared in advance. They figured help was on the way.

At 11 a.m., ABC News reported that some New Orleans levees had been breached, and a few other outlets broadcast similarly sketchy reports that day. But most of the early coverage suggested that New Orleans had dodged a bullet as Katrina's strongest gusts had passed east of the city. Wagenaar finally confirmed the levee breaches during an overflight that evening, but his agency's first post-Katrina news release boasted about the performance of its infrastructure: "The fact that Katrina didn't cause more damage is a testament to the structural integrity of the hurricane levee protection system."

At the White House, one official recalled, "there was a general sigh of relief." On a trip to Arizona, the president shared a birthday cake with Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), who was turning 69. During a speech about the Medicare drug plan, Bush noted that he had just spoken to Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff -- about immigration.

The federal interagency team seemed to recognize the urgency of the crisis at a meeting that morning, discussing the potential for six months of flooding in New Orleans, and a preliminary Department of Energy conclusion that as many as 2,000 of 6,500 oil and gas platforms in the Gulf could be affected. But before noon, FEMA's Brown sent a remarkably mild memo to Chertoff, politely requesting 1,000 employees to be ready to head south "within 48 hours." Brown's memo suggested that recruits bring mosquito repellent, sunscreen and cash, because "ATMs may not be working."

"Thank you for your consideration in helping us meet our responsibilities in this near catastrophic event," Brown concluded.

At the U.S. military's Northern Command, officers had been watching the storm since early in the week and had started sending Army brigade commanders and their staffs to the three affected Gulf states by Thursday. "We were all watching the evacuation," Maj. Gen. Richard Rowe, Northcom's top operations officer, recalled. "We knew that it would be among the worst storms ever to hit the United States." But on Monday, the only request the U.S. military received from FEMA was for a half-dozen helicopters.

As water poured into the city, as many as 20,000 more residents poured into the Superdome. "People started coming out of the woodwork," Ebbert said. The stadium was hot and fetid, and tempers were flaring. Ebbert said he told FEMA that night that the city would need buses to evacuate 30,000 people. "It just took a long time," he said.

State officials managed to get 60 boats to New Orleans for search-and-rescue operations by Monday night. By daybreak Tuesday, the state would have an additional 150 boats on the hunt. "We were very convinced that this thing was going to be a catastrophic event," said Bennett Landreneau, who was coordinating the state's rescue operations.

Around 6 p.m., as Governor Blanco was about to hold a news conference in Baton Rouge to discuss the damage, Blanco's communications director whispered that the president was on the line. The governor returned to a windowless office in her situation room and pleaded with the president for assistance.

"We need your help," she said. "We need everything you've got."

Tuesday, Aug. 30

'I've got a sewage problem that's going to be a medical disaster.'

Over the weekend, Texas emergency chief Jack Colley had continued to fret that the forecasts would turn out wrong and Katrina would pummel his state. "Don't worry," the hurricane center's Mayfield had assured him, "Texas is going to sit this one out." But now, it turned out, the storm was coming to Texas in another form. At 2:45 a.m., Louisiana's secretary of state for social services woke up Colley at home.

"Can you accept 25,000 people?" she asked.

Colley thought of his state's designated refuge: the Astrodome. Yes, he said. By 6 a.m., Colley's team was preparing to send Texas state troopers to escort the fleet of buses they had been assured would come soon. But they didn't know how many buses, or when, "and there were no answers that anyone could provide," said Steve McCraw, the homeland security adviser to Texas Gov. Rick Perry (R). Blanco ordered the Superdome evacuated, but Col. Jeff Smith, Louisiana's emergency preparedness chief, grew frustrated at FEMA's inability to send buses to move people out. "We'd call and say: 'Where are the buses?' " he recalled, shaking his head. "They have a tracking system and they'd say: 'We sent 349.' But we didn't see them."

By 5 a.m., Bush had already been briefed about New Orleans's rising waters, and decided that he would cut short his vacation the next day. Later that morning, the interagency group urgently commissioned new damage assessments, and local officials warned that the scale of the coastal damage could be "too extensive to calculate or summarize." Nagin declared that 80 percent of his city was underwater; after flying over New Orleans with FEMA's Brown and witnessing the widespread flooding, Blanco announced that "the devastation is greater than our worst fears."

But in public, Brown and Chertoff gave no such indication of the cataclysm, later saying they were not told until midday that the levee breaches were irreparable and would flood the city. William Lokey, FEMA's coordinator on the ground, declared that morning: "I don't want to alarm everybody that New Orleans is filling up like a bowl. That is just not happening."

That was exactly what was happening, and many state and local officials quickly concluded that the federal bureaucracy was spinning its wheels.

At the noon videoconference, several participants said, Louisiana's Smith heatedly demanded federal help. Where were the buses? At first, Smith recalled, he had asked for 450 buses, then 150 more, then an additional 500; by the end of the day, none had arrived. The first evacuees did not arrive at the Astrodome until 10 p.m. Wednesday -- on a school bus commandeered by a resourceful 20-year-old.

In Jefferson Parish, Maestri sent out an urgent call that morning for power packs in hopes of rescuing his county's faltering sewage system. "In Pam, they had said they'd have those ready on pallets so they could airlift them in, no problem," he later recalled. "It's 11 days later, and I still don't have them. I've got a sewage problem that's going to be a medical disaster like we've never seen in this country. Where's the cavalry?"

In the drowning city, chaos erupted. Looting was widespread, sometimes in full view of outnumbered police and often unarmed National Guard troops. Hundreds of New Orleans police officers quit. Others performed their duties courageously, and so did many state and federal personnel, but for now they focused on rescue and recovery. In general, the cavalry was nowhere to be seen, and everyone seemed to know it.

"As systems either were not followed or broke down, people just went to what they believed they could handle. Every man for himself," said Ghilarducci, Blanco's adviser. "You don't use the system, you don't use resources effectively and it breaks down."

The U.S. military command charged with domestic safekeeping was watching wild images from New Orleans. On their own initiative, Rowe said, Northcom staff members broached the idea of sending active-duty ground troops. They wanted to take a force of 3,000 soldiers designated to respond to a nuclear, chemical or biological attack, strip out unneeded elements such as chemical decontamination teams and send them to the Gulf Coast.

At this point, Blanco believed she had long since asked for the maximum possible help from the federal government. But the military was not specifically asked for its assistance. Blum began moving National Guard forces into the area before he was asked, but they had trouble navigating through a modern-day Atlantis.

Army Corps officials were trying to close the gaps in the levees, but their hurried efforts to stem the flow were hampered by a lack of supplies. They could not find 10-ton sandbags or the slings they needed to drop the bags from helicopters; most of their personnel had evacuated, and so had their local contractors. "We didn't expect any breaches," Dan Hitchings of the agency's Mississippi Valley Division later explained. "We didn't think we were going to have a wall down." The corps tried to drop smaller sandbags into the 17th Street breach, but they simply floated away with the current.

FEMA managed to deliver 65,000 meals to the Superdome, but by the end of the day, water was rising so fast that the agency was unable to unload five more truckloads of food and water. That evening, in a belated bow to televised reality, Chertoff declared the unfolding disaster an "incident of national significance," triggering the government's highest level of response for the first time since the new post-9/11 system had been designed. He did not publicly announce the move until the next day.

Wednesday, Aug. 31

'They didn't have a full sense of what they were dealing with.'

Dawn found a handful of buses outside the Superdome, and an estimated 23,000 people clamoring for a ride. FEMA had promised hundreds of buses, but they were arriving, Louisiana's Smith recalled, "in a trickle." And unbeknownst to FEMA, a new circle of hell was opening downtown, as the New Orleans convention center filled with an estimated 25,000 evacuees, many of them unable to get to the flooded area around the Superdome. There was no food, no water and no feds. A spree of robbery, looting and gunfire erupted inside as police dispatched to the center stayed almost exclusively on the perimeter, according to police and witnesses, outnumbered and unable to quell the mayhem.

New Orleans as a city had all but ceased to exist. Nagin spoke of "thousands" dead. Blanco publicly pleaded for 40,000 National Guard troops. In a conference call with Guard officials in the region, Blum asked if they had what they needed. They said no.

"They said that this is bigger than anything we've ever seen or imagined," Blum recalled. "This had touched them personally. Even at that time they didn't have a full sense of what they were dealing with." Blum immediately arranged a videoconference with every adjutant general around the country, and 3,000 Guard troops streamed into New Orleans over the next 24 hours, enough to replace the entire city police force. By Saturday, the Guard would have 30,000 troops in the region.

Bush, winging his way back from vacation, paused to swoop low over the prostrate city on Air Force One. Back in Washington, he convened a stunned Cabinet.

Bush came in with a "sense of urgency in his tone" after his aerial tour, recalled Mike Leavitt, the secretary of health and human services. "It was, 'Has anybody thought of that, who's doing this? I want you to do this and this and this.' " But the scale of the problem seemed inexplicably massive, and the plans they drew up that day would take agonizing days to carry out. Leavitt, for example, declared a federal health emergency throughout the Gulf Coast, calling for 2,500 additional hospital beds in the region by Friday, and another 2,500 in the 72 hours after that. "We had to scramble the jets," he said.

At the interagency coordination meetings, gargantuan new proposals were being discussed, such as housing the estimated million-plus newly homeless in tent cities, mobile home parks and even federalized cruise ships. At Northcom, officials were still waiting for a call requesting active-duty troops. The Navy dispatched three aid ships from Norfolk; they were due to arrive Sept. 4.

But assistance that was available was often blocked. In the Gulf, not 100 miles away from New Orleans, sat the 844-foot USS Bataan, equipped with six operating rooms and beds for 600 patients. Starting Wednesday, Amtrak offered to run a twice-a-day shuttle for as many as 600 evacuees from a rail yard west of New Orleans to Lafayette, La. The first run was not organized until Saturday. Officials then told Amtrak they would not require any more trains.

Out of public view, the White House was considering an outright federal takeover of the emergency efforts, escalating a partisan feud with the Democratic governor as Bush aides questioned her ability to manage the crisis. Despite days of pleading, the White House argued that her plea for more troops had come in only at 7:21 that morning. Amid the reports of looting and general lawlessness, the White House instructed lawyers in the Justice Department and other agencies to investigate invoking the Insurrection Act, last used during the 1992 Los Angeles riots.

But a fierce debate erupted, said an administration official who participated in the meetings and who spoke on the condition of anonymity, centering on whether Bush could order a federal takeover of the relief effort with or without Blanco's approval. White House Chief of Staff Andrew H. Card Jr., recalled from his Maine vacation, broached the question with Blanco, a senior White House official said. Later, the president called from the Oval Office to press the same idea. Both times, Blanco balked.

But her aides said she had no reason to believe the federal government would start rising to the occasion. They also said that the president never asked her directly about federalizing the state's troops. "We wouldn't have turned down federal troops," one Blanco aide said. "We were asking for them."

Thursday, Sept. 1

'They didn't hear from me . . . and they didn't come to look.'

At 4 a.m., 550 tired, hungry, frightened evacuees from the Superdome filed into Houston's Astrodome. Soon there would be thousands. Now, Houston had to figure out how to absorb not 25,000 but as many as 250,000 Louisianans.

Within hours, it was clear that many of the evacuees required urgent medical care, including 50 children from a hospital and helicopters full of soaking-wet adults.

And while initial plans had called for sheltering the entire evacuation at the Astrodome, "we found out that while you could put 23,000 people in the Dome, you wouldn't want to," as Harris County Judge Robert Eckels recalled. By evening, buses were being sent elsewhere.

Meanwhile, St. Bernard Parish was still marooned. Out of 28,000 structures in the parish, only 52 were undamaged, and as many as 5,000 were simply gone. Every day since the storm, Ingargiola had waited for the federal government to bring food, water, electricity, anything. "They didn't hear from me for four days, and they didn't come to look for us," Ingargiola recalled. "Did they think we were okay?"

Anger was also rising at federal officials, who often seemed to be getting in the way. At Louis Armstrong International Airport, commercial airlines had been flying in supplies and taking out evacuees since Monday. But on Thursday, after FEMA took over the evacuation, aviation director Roy A. Williams complained that "we are packed with evacuees and the planes are not being loaded and there are gaps of two or three hours when no planes are arriving." Eventually, he started fielding "calls from airlines saying, 'Well, we are being told by FEMA that you don't need any planes.' And of course we need planes. I had thousands of people on the concourses."

At the convention center, thousands had gathered by Thursday without supplies. There were no buses and none on the way. Nagin, almost in tears, issued a "desperate SOS."

But official Washington seemed not to be watching the televised chaos. Bush was still insisting the storm and catastrophic flooding his own government had foretold was a surprise. "I don't think anyone anticipated the breach of the levees," he said.

Later, in another television interview, Brown insisted that everything was "under control." And though the crowds had started to flock to the convention center two days earlier, Brown said: "We learned about the convention center today."

In private, Bush had reached a "tipping point" Thursday, a senior aide said, when he watched images from the convention center. But the debate inside his administration still raged over whether to federalize the Guard and take overall control of New Orleans.

At Northcom, they were still awaiting orders. That day, Rowe said, the planners had come up with another military option -- a logistical force to back up the overtaxed relief effort on the ground. The idea was to send as many as 1,500 troops each to Louisiana and Mississippi. At Fort Bragg, N.C., the 82nd Airborne was on standby to deploy, so was the First Cavalry Division at Fort Hood, Tex., and Marine bases on both coasts.

Bush discussed the idea with Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld that day, but still held back on deciding. The cavalry would have to wait.

Friday, Sept. 2

'The results are not acceptable.'

At 7 a.m., Bush called his generals to the White House, along with Rumsfeld and Chertoff. They discussed final terms of Bush's plan -- by nightfall, he would demand that Blanco hand over control of National Guard troops. And they hashed out the idea of sending in the active-duty military, though troops from the 82nd Airborne and 1st Cavalry would not get their orders until the next day.

Then Bush left for the stricken region.

Before boarding his helicopter, the president had a terse comment about his government's performance. "The results are not acceptable." But shortly after they touched down in Alabama, the president's tone changed. He turned to Brown, the focus of much of the criticism from state and local officials, and declared: "Brownie, you're doing a heck of a job."

Later in the tour, Homeland Security Secretary Chertoff visited Jefferson Parish, and told Maestri he was doing a wonderful job. "Where are the resources?" Maestri asked.

"He said: 'It's coming, it's coming,' " Maestri recalled. "Yeah, well, Christmas is coming, too." [Susan B. Glasser and Michael Grunwald The Washington Post]

<< Home