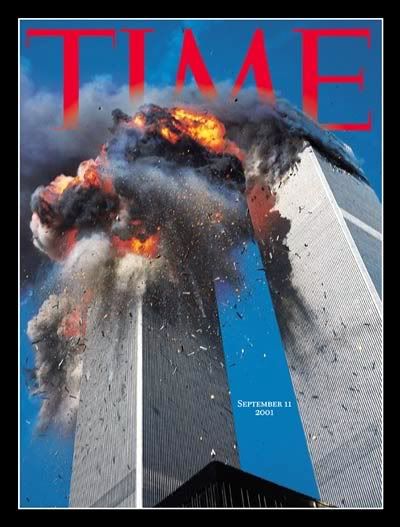

DAVID D. KIRKPATRICK/SCOTT SHANE The New York TimesWASHINGTON - Hours after Hurricane Katrina passed New Orleans on Aug. 29, as the scale of the catastrophe became clear, Michael D. Brown recalls, he placed frantic calls to his boss, Michael Chertoff, the secretary of homeland security, and to the office of the White House chief of staff, Andrew H. Card Jr.

Mr. Brown, then director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, said he told the officials in Washington that the Louisiana governor, Kathleen Babineaux Blanco, and her staff were proving incapable of organizing a coherent state effort and that his field officers in the city were reporting an "out of control" situation.

"I am having a horrible time," Mr. Brown said he told Mr. Chertoff and a White House official - either Mr. Card or his deputy, Joe Hagin - in a status report that evening. "I can't get a unified command established."

By the time of that call, he added, "I was beginning to realize things were going to hell in a handbasket" in Louisiana. A day later, Mr. Brown said, he asked the White House to take over the response effort.

He said he felt the subsequent appointment of Lt. Gen. Russel L. Honoré of the Army as the Pentagon's commander of active-duty forces began to turn the situation around.

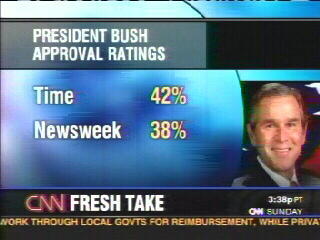

In his first extensive interview since resigning as FEMA director on Monday under intense criticism, Mr. Brown declined to blame President Bush or the White House for his removal or for the flawed response.

"I truly believed the White House was not at fault here," he said.

He focused much of his criticism on Governor Blanco, contrasting what he described as her confused response with far more agile mobilizations in Mississippi and Alabama, as well as in Florida during last year's hurricanes.

But Mr. Brown's account, in which he described making "a blur of calls" all week to Mr. Chertoff, Mr. Card and Mr. Hagin, suggested that Mr. Bush, or at least his top aides, were informed early and repeatedly by the top federal official at the scene that state and local authorities were overwhelmed and that the overall response was going badly.

A senior administration official said Wednesday night that White House officials recalled the conversations with Mr. Brown but did not believe they had the urgency or desperation he described in the interview.

"There's a general recollection of him saying, 'They're going to need more help,' " said the official, who insisted on anonymity because of the delicacy of internal White House discussions.

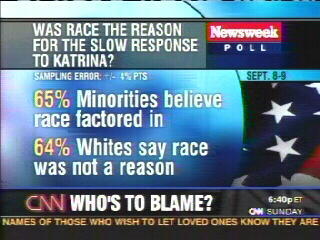

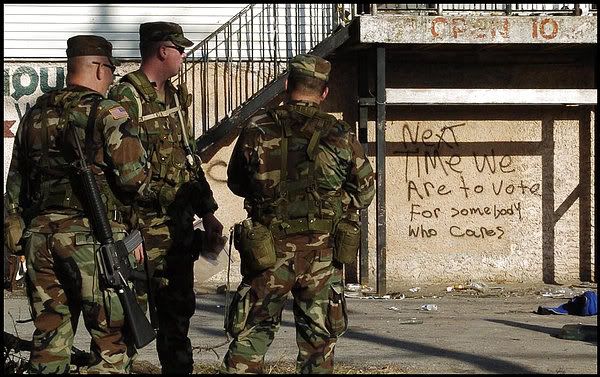

Mr. Brown's version of events raises questions about whether the White House and Mr. Chertoff acted aggressively enough in the response. New Orleans convulsed in looting and violence after the hurricane, and troops did not arrive in force to restore order until five days later.

The account also suggests that responsibility for the failure may go well beyond Mr. Brown, who has been widely pilloried as an inexperienced manager who previously oversaw horse show judges.

Mr. Brown was removed by Mr. Chertoff last week from directing the relief effort. A 50-year-old lawyer and Republican activist who joined FEMA as general counsel in 2001, Mr. Brown said he had been hobbled by limitations on the power of the agency to command resources.

With only 2,600 employees nationwide, he said, FEMA must rely on state workers, the National Guard, private contractors and other federal agencies to supply manpower and equipment.

He said his biggest mistake was in waiting until the end of the day on Aug. 30 to ask the White House explicitly to take over the response from FEMA and state officials.

Of his resignation, Mr. Brown said: "I said I was leaving because I don't want to be a distraction. I want to focus on what happened here and the issues that this raises."

Governor Blanco said Wednesday that she took responsibility for failures and missteps in the immediate response to the hurricane and pledged a united effort to rebuild areas ravaged by the storm, adding, "at the state level, we must take a careful look at what went wrong and make sure it never happens again." A spokesman for Ms. Blanco denied Mr. Brown's description of disarray in Louisiana's emergency response operation. "That is just totally inaccurate," said Bob Mann, the governor's communications director. "Everything that Mr. Brown needed in terms of resources or information from the state, he had those available to him."

In Washington, Mr. Chertoff's spokesman, Russ Knocke, said there had been no delay in the federal response. "We pushed absolutely everything we could," Mr. Knocke said, "every employee, every asset, every effort, to save and sustain lives."

As Mr. Brown recounted it, the weekend before New Orleans's levees burst, FEMA sent an emergency response team of 10 or 20 people to Louisiana to review evacuation plans with local officials.

By Saturday afternoon, many residents were leaving. But as the hurricane approached early on Sunday, Mr. Brown said he grew so frustrated with the failure of local authorities to make the evacuation mandatory that he asked Mr. Bush for help.

"Would you please call the mayor and tell him to ask people to evacuate?" Mr. Brown said he asked Mr. Bush in a phone call.

"Mike, you want me to call the mayor?" the president responded in surprise, Mr. Brown said. Moments later, apparently on his own, the mayor, C. Ray Nagin, held a news conference to announce a mandatory evacuation, but it was too late, Mr. Brown said. Plans said it would take at least 72 hours to get everyone out.

When he arrived in Baton Rouge on Sunday evening, Mr. Brown said, he was concerned about the lack of coordinated response from Governor Blanco and Maj. Gen. Bennett C. Landreneau, the adjutant general of the Louisiana National Guard.

"What do you need? Help me help you," Mr. Brown said he asked them. "The response was like, 'Let us find out,' and then I never received specific requests for specific things that needed doing."

The most responsive person he could find, Mr. Brown said, was Governor Blanco's husband, Raymond. "He would try to go find stuff out for me," Mr. Brown said.

Governor Blanco's communications director, Mr. Mann, said that she was frustrated that Mr. Brown and others at FEMA wanted itemized requests before acting. "It was like walking into an emergency room bleeding profusely and being expected to instruct the doctors how to treat you," he said.

On Monday night, Mr. Brown said, he reported his growing worries to Mr. Chertoff and the White House. He said he did not ask for federal active-duty troops to be deployed because he assumed his superiors in Washington were doing all they could. Instead, he said, he repeated a dozen times, "I cannot get a unified command established."

The next morning, Mr. Brown said, he and Governor Blanco decided to take a helicopter into New Orleans to see the mayor and assess the situation. But before the helicopter took off, his field coordinating officer, or F.C.O., called from the city on a satellite phone. "It is getting out of control down here; the levee has broken," the staff member told him, he said.

The crowd in the Superdome, the city's shelter of last resort, was already larger than expected. But Mr. Brown said he was relieved to see that the mayor had a detailed list of priorities, starting with help to evacuate the Superdome.

Mr. Brown passed the list on to the state emergency operations center in Baton Rouge, but when he returned that evening he was surprised to find that nothing had been done.

"I am just screaming at my F.C.O., 'Where are the helicopters?' " he recalled. " 'Where is the National Guard? Where is all the stuff that the mayor wanted?' "

FEMA, he said, had no helicopters and only a few communications trucks. The agency typically depends on state resources, a system he said worked well in the other Gulf Coast states and in Florida last year.

Meanwhile, "unbeknownst to me," Mr. Brown said, at some point on Monday or Tuesday the hotels started directing their remaining guests to the convention center - something neither FEMA nor local officials had planned.

At the same time, the Superdome was degenerating into "gunfire and anarchy," and on Tuesday the FEMA staff and medical team in New Orleans called to say they were leaving for their own safety.

That night, Mr. Brown said, he called Mr. Chertoff and the White House again in desperation. "Guys, this is bigger than what we can handle," he told them, he said. "This is bigger than what FEMA can do. I am asking for help."

"Maybe I should have screamed 12 hours earlier," Mr. Brown said in the interview. "But that is hindsight. We were still trying to make things work."

By Wednesday morning, Mr. Brown said, he learned that General Honoré was on his way. While the general did not have responsibility for the entire relief effort and the Guard, his commanding manner helped mobilize the state's efforts.

"Honoré shows up and he and I have a phone conversation," Mr. Brown said. "He gets the message, and, boom, it starts happening."

Mr. Brown said that in one much-publicized gaffe - his repeated statement on live television on Thursday night, Sept. 1, that he had just learned that day of thousands of people at New Orleans's convention center without food or water - "I just absolutely misspoke." In fact, he said, he learned about the evacuees there from the first media reports more than 24 hours earlier, but the reports conflicted with information from local authorities and he had no staff on the site until Thursday.

There were also conflicts with the Congressional delegations that wanted resources for their offices and districts, FEMA officials said. Senator Trent Lott of Mississippi said he "resisted aggressively" a decision by Mr. Brown to dispatch a Navy medical ship to Louisiana instead of his home state.

Mr. Brown acknowledged that he had been criticized for not ordering a complete evacuation or calling in federal troops sooner. But he said the storm made it hard to communicate and assess the situation.

"Until you have been there," he said, "you don't realize it is the middle of a hurricane."

Où s'arrêteront les constructeur automobiles japonais? Nissan vient de faire sensation en présentant à Tokyo son dernier concept-car, le «Pivo». Une voiture électrique, équipée d'une batterie en lithium et capable d'atteindre les 80 km/h. Jusqu'ici, rien de révolutionnaire. Mais l'engin repose sur un concept étonnant: une cabine en forme d'œuf, qui peut pivoter de 360 degrés sur une plate-forme équipée de roues afin de faciliter les manœuvres. Plus besoin de faire marche arrière: le «Pivo» peut rouler indifféremment dans un sens comme dans l'autre, selon la position de la cabine. Il peut se garer dans des créneaux serrés et fonctionne selon un système expérimental de conduite par commande électronique. «Grâce à une technologie filaire de Nissan, nous avons supprimé le contact mécanique entre la cabine et le châssis», a expliqué Hidetoshi Kadota, un des directeurs de la division d'ingénierie avancée du constructeur. A l'extérieur du véhicule, quatre caméras vidéo éliminent les angles morts. On pourra observer l'engin du 22 octobre au 6 novembre, au salon Tokyo Motor Show. (Libération.fr)

Où s'arrêteront les constructeur automobiles japonais? Nissan vient de faire sensation en présentant à Tokyo son dernier concept-car, le «Pivo». Une voiture électrique, équipée d'une batterie en lithium et capable d'atteindre les 80 km/h. Jusqu'ici, rien de révolutionnaire. Mais l'engin repose sur un concept étonnant: une cabine en forme d'œuf, qui peut pivoter de 360 degrés sur une plate-forme équipée de roues afin de faciliter les manœuvres. Plus besoin de faire marche arrière: le «Pivo» peut rouler indifféremment dans un sens comme dans l'autre, selon la position de la cabine. Il peut se garer dans des créneaux serrés et fonctionne selon un système expérimental de conduite par commande électronique. «Grâce à une technologie filaire de Nissan, nous avons supprimé le contact mécanique entre la cabine et le châssis», a expliqué Hidetoshi Kadota, un des directeurs de la division d'ingénierie avancée du constructeur. A l'extérieur du véhicule, quatre caméras vidéo éliminent les angles morts. On pourra observer l'engin du 22 octobre au 6 novembre, au salon Tokyo Motor Show. (Libération.fr)